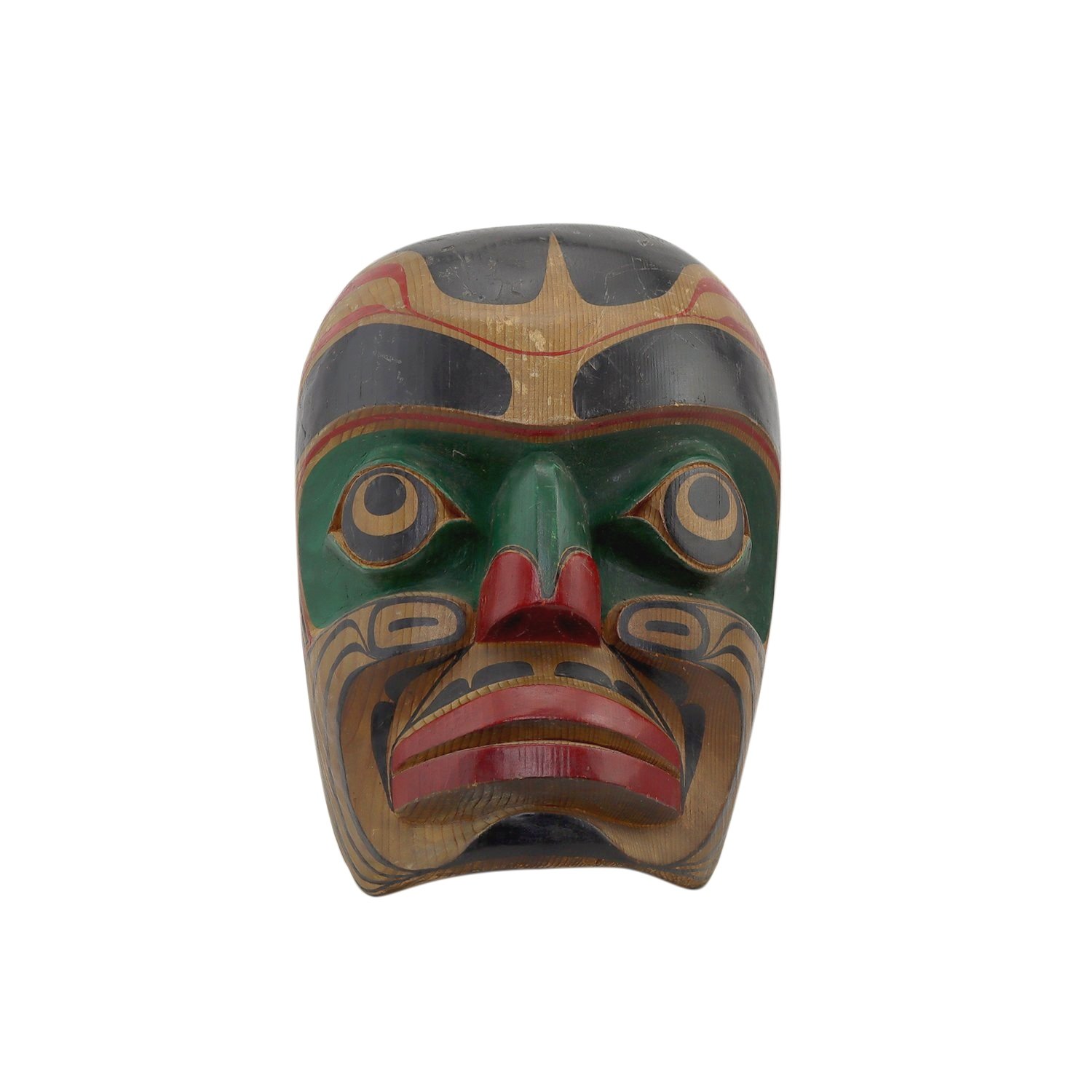

ELLEN NEEL

(Kwakwaka'wakw (Kwakiutl) 1916-1966)

AVAILABLE WORKS

SELECT SOLD

BIOGRAPHY

Ellen Neel was born in Alert Bay on November 14, 1916. The daughter of Charlie Newman and Lucy Lilac James (Lalaxs’a), and granddaughter of renowned master carver Yakuglas/Charlie James, to whom she was very close. Ellen attended St. Michael’s School in Alert Bay and spent her free time with her grandfather, who took care of her while her mother was ill. From him, she learned learned the basics of Northwest Coast design and the rudiments of Kwakwaka'wakw carving, and collaborated with him on a book of designs. By the age of 12, Ellen was selling her work to tourists who stopped at Alert Bay en route to Alaska. She is considered the first trained woman carver on the Northwest Coast, studying under her grandfather while there was still a ban on the Northwest Coast potlatch. Breaking down many barriers and carving herself a place in a tradition primarily dominated by males, she embraced new materials and forms and would have a major part in the resurgence of traditional stylization. Known as “Ellen-Ah”, her Kwakwaka’wakw name was KaKaso’las meaning that ‘people came from far away to seek her advice’, which reflected her good humour and positive outlook.

Ellen married the metal worker and salesman Ted Neel, and in 1943 the couple moved their family from Alert Bay to Vancouver where Ted operated a small machine shop. Ellen had seven children: Dave (born 1937), Ted Jr. and Bob (both born 1939), Cora (born 1941), Theo (born 1944), Pamela (born 1945), and Theresa who was nicknamed Bitty (born 1947). The children received proper Kwakiutl names from Ellen’s uncle, Mungo Martin during a 1953 potlatch held in Thunderbird Park in Victoria, the first public potlatch since 1921, which resulted in a number of people being prosecuted. Ellen carved intermittently but the couple lived pay cheque to pay cheque. In 1946 Ted suffered a series of strokes which left his health impaired and Ellen as the main breadwinner. The couple embarked on a joint business venture, with Ellen designing, carving and painting and Ted handling the sales, supplies and business side. They converted their home on Powell Street into a joint studio workshop where Ellen worked and store where the tourist poles were marketed.

Harry Duker, a self-appointed publicity agent for the City of Vancouver, devoted himself to attracting tourists to Vancouver. He formalized the name "Totemland" by forming the Totemland Society which publicized the City of Vancouver, and Ellen was commissioned to design its insignia. What came to be known as the "Totemland Pole" was a kneeling figure representing the first man, a globe of the world featuring the Coast of B.C., topped by a thunderbird with wings outspread. The pole was widely publicized on textiles, t-shirts etc, and became Duker's personal trademark. Duker verbally arranged for the Neel family to begin carving and sell works in Stanley Park where the couple set up a tent. Ellen designed a series of tourist poles and carvings and the enterprise took off. During this time the children became involved in the production of the tourist poles.

The anthropologist and ethnographer Marius Barbeau contacted Ellen in 1947 seeking information on her grandfather, Charlie James, for his publication “Totem Poles”. The following spring Ellen was invited as guest speaker to address the subject of Indian art and its potential commercial market at the UBC conference on Native Indian Affairs. Her speech described her thoughts on the golden age of totem art: “the art is a living symbol of the gaiety, the laughter, and the love of colour of my people…”, and how the interest of the tourist trade, the universities and the museums, fueled the resurgence of the creativity of the native people. As a result of this the Vancouver Parks Board set up a large workshop at Third Beach in Stanley Park where Ellen could sell her work and teach carving to other artists. That summer Ellen and her sons worked on a large pole at the Pacific National Exhibition, often signing cedar ‘totem pole’ chips for the public. The family business, named Totem Art Studios, was busy, as orders for tourist poles as well as commissioned pieces rose. The same year a 16’ Thunderbird totem was carved for the Alma Mater Society of UBC, presented at the UBC by Chief William Scow of Alert Bay as a gift from Ellen and Ted to the University, along with the right to use the name “Thunderbird’ for the football team.

Totem Art Studios was contracted to begin restorations for the Department of Anthropology at UBC on a number of Kwakwaka’wakw totem poles. Despite the busy tourist season Ellen agreed to take on the restoration project, tackling 4 large poles from Fort Rupert including one carved by her grandfather, Charlie James. The difficulty of the restoration process prompted the idea of copying the old poles, many in advanced stages of deterioration, leaving them in situ for later study. The advantage of producing new replicas poles to be erected for future enjoyment was enthusiastically embraced. Ellen engaged the skills of her uncle, Mungo Martin, Charlie James’ stepson, a master carver of poles who trained in the same school as Ellen, who took over her work at UBC.

Ellen refocused her efforts on the family business, yet a decline in sales prompted Ellen and Ted to stop carving at the Ferguson Point workshop and only use the location for summer sales. Ellen’s focused shifted from large poles and commissioned pieces while the family increased the output of souvenir and tourist works with the children all contributing. Ellen designed a line of poles in various sizes ranging from 6-18” based on the same basic pole using the thunderbird with spread wings on top and alternating the bottom with the Dxunukwa (wild woman of the woods), the killer whale and the bear, complete with a base. The children were involved in production, the older boys doing the bulk of the carving up to the finish sanding with Ellen completing the painting. The basement of the house on Glen Drive was converted into a workshop, with the addition of a studio nearby. A retail price list and illustrated product description was created for Totem Art Studios and distributed across the country. The following years were dedicated to commercial sales; in 1954 an inventory was made which included over 1200 objects. During this time the house was visited by many friends and family including Reg Ashwell, Jimmy John, Bill Reid, Mungo Martin and the artist Mildred Valley Thornton. It was during this time that Ellen took on the keen 12-year old Phil Nuytten as an apprentice, who learned carving from working with Ellen and her boys, specifically the eldest David, and Mungo Martin.

Ellen received many prominent commissions, including the decor of the foyer for the new Harrison Hot Springs Hotel, which enabled her to integrate her detailed carvings including two eleven-foot totems and many smaller pieces. She held public office, and was a regular contributor to The Native Voice magazine. In the fall of 1950 her work was represented at a Montreal Museum of Fine Arts exhibition, and the following year a Totem Art Studios pole was highlighted on a tv programme “The Show Goes On”, as well as an intricate pole was presented as a wedding present to Lord and Lady Selkirk in London. 1951 Ellen’s work was exhibited at an international trade fair in Toronto. A Copenhagen museum commissioned a large totem in 1953, and the following year a 5’ totem for a Boy Scouts Group in Wales. Ellen secured a contract with Royal Albert China for her Totemware China pattern, featuring her Totemland pole design and her grandfather’s house posts which stood in Stanley Park. The Totemware China line was produced first in black and white and then in colour, and sold in souvenir shops in B.C., Alberta and Alaska.

A major commission of 5 poles for the Westmount Mall in Edmonton were completed in a shed at Ferguson Point in 1955, the last summer the family would work together. The Neel family moved from the house on Glen Drive to Antrim Street in Burnaby and David moved out to pursue his own carving career, followed by Cora and Bob. By 1959 the family lived in White Rock with a planned move to Aldergrove in 1960. Ellen and Ted were invited to Stratford, Ontario to demonstrate the carving of a 22’ pole during the Stratford Summer Festival, for presentation to a collector in Michigan. Beside the carving demonstration was a large display of Northwest Coast art on loan from the National Gallery in Ottawa, as well as Emily Carr paintings depicting BC Coast villages from the Vancouver Art Gallery. The ‘living art’ display was the focal point of the festival and widely publicized. At seventeen, Theresa (Bitty) Neel was brought along to handle the public relations, including a one-hour interview with CBC. The event resulted in enthusiastic response and several commissions, including the O’Keefe Conservation Trophy.

Ellen’s health was deteriorating and created problems with her eyes, and she completed the trophy despite a visit to hospital. By 1961 she had recurring bouts of illness and fatigue. Theo had left home and only Ted Jr and Bitty remained with Ellen and Ted in Aldergrove. In September 1961, David’s death in a car crash devastated the family and especially Ellen. As Ellen’s health declined and she became bedridden, and the couple’s economic burdens further increased. The family could offer limited help in completing commissions, and quality diminished. Friends tried to help, including Harold Lando of Lando’s furs and David Lambert of Lambert’s Potteries. Encouraged to seek help from the government, in 1963 applied for a Canada Council grant, but unfortunately was turned down. The family struggled to produce and sell their work, and one by one sold off treasures Ellen had brought with her from her childhood in Alert Bay, including the original watercolour paintings done by Ellen and her grandfather Charlie James, and then the sketchbooks and Charlie James poles that Ellen had kept as reference.

Ellen was hospitalized in January, 1966 and died at Vancouver General Hospital on February 3. Part of Ellen’s ashes were scattered over Johnstone Strait, the mouth of the Nimpkish River, and the Cluxewe River near Port McNeil, the rest returned to Alert Bay for burial. Artist Mildred Valley Thornton said of her friend “I admired her as a woman and honoured her and respected her as an artist – she was a most self-sacrificing woman who kept her family through her art. She was gentle and kind, and loving in every way as an individual. She was a great credit to Canada and to her own people.” Ellen Neel’s legacy is carried on by her children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.